Long before the era of COVID-19, Laura Kasbar was a Spokane mother who merely wanted to find a way to address her children’s autism.

Almost by chance, she noticed that video lessons would help, particularly with a child who doctors had declared would never speak.

Nine years later, in 2011, her son Max was mainstreamed, and her Gemiini Systems, still based in Spokane, has become a worldwide leader in online distance learning for people with autism, Down syndrome, dyslexia, speech delay, stroke and other issues.

Since the novel coronavirus outbreak, Gemiini has seen “an avalanche” of interest as families and school districts seek virtual solutions to real-life challenges of learning from home, Kasbar said from her home in Southern California.

The company, with about 50 employees, is run by her son Nicholas out of the Holley- Mason Building in downtown Spokane. After an initial adjustment, Gemiini has adapted to a surge in business.

Gemiini has opened its certification program to professionals and has waived the $490 fee for certification.

Gemiini is also offering schools and clinics the use of its system at no cost as long as they agree to submit the cost of the program to Medicaid.

Gemiini has proven to be a valuable solution for special education administrators, who are struggling to navigate this crisis to continue to meet the needs of special needs students and families.

For many children, “this can be the only link to therapy,” Kasbar said. “And now with COVID everyone is on that boat.

“Our team has been able to get to work immediately. Our subscription base has increased dramatically.”

Gemiini – the unique spelling is Kasbar’s tribute to her autistic twins, Max and Anastasia – was the product of Kasbar’s yearslong search for a solution.

Nicholas Kasbar is ready for a busy day at Gemiini Educational Systems located in the Holley-Mason Building in downtown Spokane. Gemiini Educational Systems, which Kasbar co-founded with his mother Laura, is a video-focused system to teach autistic children. Business is booming for Gemiini since the COVID-19 pandemic sent students home for school.

It was in 2001 that Kasbar recalled walking into a room in her Spokane home, saw all six of her children lined up in front of the television and “couldn’t really tell which were the autistic ones.”

At that time, conventional wisdom dictated the television should be turned off if autistic children were nearby. But that experience told Kasbar video was the answer.

She and her husband Brian had noticed that young Max wouldn’t make eye contact with them but would interact with the television.

“I thought, ‘I’ve got to get my mouth on the TV,’ ” Kasbar said.

That night, they made one-minute videos of a cup and Barney, the TV dinosaur.

“It was a close-up of my mouth saying the word ‘Barney’ next to the actual Barney and then saying the word ‘cup’ next to a cup. We did three sets in a row,” Kasbar said.

That night, after watching several times from his highchair while eating, Max made his biggest breakthrough.

Kasbar held up a cup and he said “cup,” his first word – 3 years and 8 months of age.

During the next decade, and with the help of her oldest son, Nicolas – who also had been on the autism spectrum – Kasbar developed the video program.

In 2012, thanks to funding from the Spokane Angel Alliance and Inland Imaging, Gemiini was launched.

Backed by studies from four universities, Gemiini serves 30,000 clients in 40 countries.

Its use of discrete video modeling, which presents only a specific piece of audio information, was showed by a Portland State University study to be 300% more effective than standard video modeling.

Kasbar was so inspired by the success of her program that she shared her experiences in a book, “Embracing the Battle: Secrets of Victory from a Warrior Mom.”

Closer to home, Gemiini has worked with former NFL star and Spokane native Mark Rypien to develop an application to address suicide prevention.

The goal, Rypien said last fall, is to connect circles of friends of persons at risk so they can better monitor their state of mind.

Lately, the main focus has been reaching children who have been isolated by COVID-19.

“It’s been pretty easy,” said Nicolas, who runs the Spokane headquarters. “After a few headaches, we’ve been able to keep going and helping people, and we’ve updated a lot of our instructions on Facebook Live to walk people through how our lessons work.”

Jim Allen can be reached at (509) 459-5437 or by email at [email protected].

First published in the Journal of Business, June 4, 2020. By Kevin Blocker.

Not even the COVID-19 pandemic has been able to blunt the tide of growth the design-build construction company Verdis is experiencing.

Since becoming a member of the Small Business Administration’s 8(a) Business Development Program in 2016, Verdis has secured 99 federal projects, 19 of which are currently active, says Sandy Young, founder and principal of the Coeur d’Alene-based company.

Verdis founder and principal Sandy Young, left, sits with senior planner Stephanie Blalack in the company’s offices in the Parkside Tower, in downtown Coeur d’Alene.

The 8(a) program is a nine-year business development program that provides business training, counseling, marketing, and technical assistance to small businesses that have applied and then been accepted to the program.

Verdis has a greater ability to secure federal work with certifications as both a woman-owned business and an 8(a) operation. The federal government’s goal is to award at least 5% of all federal contracting dollars to small businesses and women- and minority-owned businesses.

Now doing business in 13 western states, Verdis recently secured its largest federal contract to date, an almost $4 million project in Alaska, where Young is from originally.

A 7.1-magnitude earthquake that struck south central Alaska on Nov. 30, 2018, continues to generate engineering and construction repair work through the federal pipeline.

Despite the flourishing federal work, Young says one of the requirements of 8(a) status is to maintain local work in the community. While she declines to disclose the firm’s annual revenue, she says close to a third of all income is generated by local projects.

Deemed as an essential business, Verdis anticipates annual revenue to double in 2020 over 2019. First-quarter revenue alone this year exceeded calendar year 2019, she says.

The company forecasts a nearly four-fold increase in revenue by 2022, compared with 2019 earnings, Young says.

“We’ve been able to self-perform much of our work, which is a big deal for an 8(a),” she says. “Very few firms do both engineering and construction. We seal fish ladders, rip up rails in powerhouses at dams, and restore old buildings and windows.”

With 25 employees, Verdis occupies roughly 2,000-square feet of space in a second-floor suite at Parkside Tower, located at 601 E. Front. It’s the company’s fifth location since its founding in 2007, Young says.

A vice president of construction, Colin Meehan, oversees five project superintendents and six members of a field-personnel team, constituting the firm’s largest concentration of employees.

Young, who is 64, moved to Idaho from Alaska in 1997 and spent the next decade working in Kootenai County’s community development department. Along the way, she met her late husband, Gary, who worked as the director of community development for the city of Post Falls, she says.

The two married in 2006, and the following year, Young says the couple began the process of going into business for themselves.

“He had been in business for himself for a while; he was a licensed landscape architect,” she says. “He’d say, ‘It’s not as easy you think, not every hour is billable.’ I remember sitting on a plane—we were going on a trip somewhere—and telling him, ‘Let’s do it.’’’

In the basement of a building in Post Falls, the couple set up an independent development and planning operation.

“Fortunately, because of our public-sector jobs, people knew us,” she says. “There weren’t many planners around, so we got a few clients right out of the gate.”

Young says the company steadily grew. Landscape architecture work quickly expanded, and Verdis began using subcontractors for civil engineering projects.

In 2012, Verdis was granted woman-owned business status through the SBA, but the business didn’t qualify for the 8(a) program due to the couple’s combined assets, she says.

Then, in 2014, Gary Young contracted cancer and died the following year. It was his death that allowed Verdis to qualify for 8(a) status, she says.

“On his death bed he said, ‘Get the 8(a). I want you to kill it. I don’t want to have to worry about you,’’’ Sandy Young says, fighting back tears.

Reflecting on that time, Young says the business took off as she poured herself into work as way to deal with the grief.

“That wouldn’t have happened if I would’ve had a spouse at home, right?” she asks rhetorically. “Who doesn’t want to be home at night?”

Young says she bought a new car and “hit the road” religiously in an effort to generate new business.

“Honestly, it seemed like such a longshot because you’re sitting there trying to sell your capability, and I really didn’t understand the world I was in,” she says. “We didn’t have any idea how to put a bid together, we didn’t know what we were going to do. We were designers.”

As Young tried to recruit clients, she was asked if Verdis did construction work. Upon answering no, she was met with a consistent message: Come back when you do.

“Three times I heard that. The fourth time I was asked, my answer was, ‘You bet we do,’’’ she says. “I came back and told staff we’re going to figure this out.”

A year later, Verdis secured its first federal contract, a $327,000 Kachess River Bridge project in Cle Elum, Washington, Young says.

Stephanie Blalack, a senior planner with Verdis, has a perspective about Young and the firm, unlike any other employee. She is the company’s first hire.

“I hired Steph out of college (2004) when I still worked for Kootenai County,” Young says. “When I jumped ship, I brought her with me.”

Says Blalack, “She was a phenomenal boss at the county, so when she left in 2007, I was just devastated.”

Seven months later, Young reached out to her with a job offer.

“I was 25, 26, and I’m thinking of leaving my government job? My parents were like, ‘Are you crazy?’’’ says Blalack.

“But I just had this feeling that I knew she was going to make it,” she says. “If it were anybody else, I would not have left my government job.”

Contact author at [email protected] or 509.344.1267

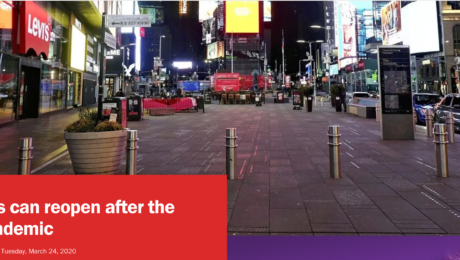

As the dreaded coronavirus rips across the globe, city after city has locked down, transforming urban business centers, suburban malls, and other public spaces into ghost towns. This is not the first time this has happened—since time immemorial, cities have been epicenters of communicable diseases.

No pandemic or plague or natural disaster has killed off “the city,” or humanity’s need to live and work in urban clusters. Not the Black Plagues of the 14th century, or London’s cholera epidemic in the 1850s, or even 1918’s Spanish Flu, which killed tens of millions of people worldwide. That’s because cities’ concentration of people and economic activity—which serves as the motor force for innovation and economic growth—is just too strong.

We will get through this pandemic, too. We will go back to work and school and gather in restaurants and theaters and sports stadiums again. But when we do, cities and their leaders should not simply return to business as usual. Not only does COVID-19 threaten to reappear in subsequent waves if we do not remain vigilant, but there will always be future pandemics to brace against as well.

Our mayors, governors, and community leaders must do whatever is necessary to get their cities back up and running as soon as they safely can. After, we will need plans in place to prepare for future pandemics, and any social or economic lockdowns they necessitate. The federal government must do its part too, with bold and unprecedented programs to bolster the economic situation of our states and cities as well as our workers and business, especially small business.

Getting this response right may be as important as what we are doing today. Below is a 10-point plan based on detailed tracking of the current pandemic and historical accounts of previous ones, presenting some key measures to prepare our cities, economy, and workers for the next phase of the coronavirus crisis and beyond.

- Pandemic-proof airports: Airports are a critical engine of economic development—they cannot be idled indefinitely. We need to make sure they can get up and running again quickly, and that means mobilizing like we did in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks by adding temperature checks and necessary health screenings to the security measures already in place. It also means reducing crowding: Simple things like stanchions or painted lines on floors can promote social distancing in waiting areas. Airports should have large quantities of masks and hand sanitizer available, and airlines will need to reduce their passenger counts and keep middle seats open during future health crises.

- Prepare large-scale civic assets: Cities are also home to other forms of large-scale infrastructure: stadiums, arenas, convention centers, performing arts centers, etc. Because they bring together large groups of people, city leaders must pandemic-proof these assets as much as possible, too. Audience sizes may need to be reduced in theaters, with seats left open. Masks may need to be required and made available to patrons as needed, and temperature checks carried out. This will be critical for communities that are dependent on such attractions: A Brookings analysis shows that COVID-19’s economic downturn will hit tourism-driven cities such as Orlando and Las Vegas hardest. The sooner such large-scale civic infrastructure can be safely reopened, the faster our urban economies will be able to rebound in the aftermath of a pandemic.

- Modify vital infrastructure: As we’ve seen during the first phase of the COVID-19 crisis, buses, subways, and trains need emergency infusions of cash to keep the systems solvent when ridership is low or nonexistent. When they are back in service, design changes in stations and seating will be needed to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Streets may need some retrofits too; New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has called for pedestrianizing some New York City streets to promote social distancing during COVID-19. Some of these changes should be permanent. Cities need to expand and better protect their bike lanes too, while refining bike- and scooter-sharing programs for when public transit in compromised.

- Ready key anchor institutions: Medical centers, hospitals, and universities are on the front lines of the battle against COVID-19, and many are already overtaxed. With dormitories, dining halls, and large groups of people, they will be highly vulnerable to the secondary waves of contagion. How can we ensure that they can operate safely to carry out vital research during pandemics? Just as with other large-scale civic assets, classes in these institutions can be kept small, but institutions will need to retrofit dormitories and dining halls with temperature checks and ensure adequate social distancing so they can safely function.

- Embrace telework: We are in the midst of a massive experiment in remote work. Most people will eventually go back to their offices, but some workers and companies may find remote work to be more effective. Tulsa, Okla. has leveraged this concept through its Tulsa Remote initiative, which pays remote workers a small grant to relocate there while helping them forge community and civic connections. Cities can learn from one another about how to best support the growing cadre of remote workers and make them connected, engaged, and vital parts of their communities.

- Ensure Main Street survives: The restaurants, bars, specialty shops, hardware stores, and other mom and pop shops that create jobs and lend unique character to our cities are at severe economic risk right now. Some projections suggest that as many as 75% of them may not survive the current crisis. The loss of our Main Street businesses would be irreparable, and not just for the people whose livelihoods depend on them, but for cities and communities as a whole. The places that have protected their Main Streets will have a decisive competitive advantage as we return to normalcy. Loan programs from government, foundations, and the private sector as well as support from small business and technical organizations will be essential for ensuring these businesses survive. Cities need to provide this type of assistance and advice to these vital small businesses so they can safely reopen and weather the storm of future lockdowns.

- Protect the arts and creative economy: The creative economy of art galleries, museums, theaters, and music venues—along with the artists, musicians, and actors who fuel them—is also at dire risk. Cities must partner with other levels of government, the private sector, and philanthropies to marshal the funding and expertise needed to keep their cultural scenes alive. Once they are allowed to reopen, these places will also need to make interim and long-term changes in the way they operate. Cities should provide advice and assistance on necessary procedures—from temperature screenings, better spacing for social distancing, and other safety measures—for these venues to continue as part of the urban landscape.

- Assess leading industries and clusters: It’s not individual firms but clusters of industry and talent that drive economic development. Some of those clusters are at greater risk than others: Sectors such as transportation, travel and hospitality, and the creative arts will be hit the hardest, while e-commerce and distribution or advanced manufacturing for health care and food processing may grow. Cities and economic development organizations must assess the industries and clusters that are most vulnerable in their territory, evaluate the impacts future pandemics will have for their labor markets and communities, and plan to make their economies more resilient and robust. They should pull together cluster working groups of business and non-profit representatives and local academics and experts to best assess the impact of the pandemic and pandemic-related response on key clusters and develop medium-range plans.

- Upgrade jobs for front-line service workers: Nearly half of Americans work in low-wage service jobs. A considerable percentage of them—emergency responders, health care aides, office and hospital cleaners, grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, delivery people—are on the front lines of the pandemic. They need better protection, higher pay, and more benefits. States such as Vermont and Minnesota have paved the way by designating grocery store employees as emergency workers, making them eligible for benefits including free child care. Having a well-paid cadre of front-line service workers who can keep our communities safe and functional will help protect us from future wave of this pandemic and others that may follow.

- Protect less-advantaged communities: The economic fallout of pandemics will hurt most for the least-advantaged neighborhoods and their residents, who lack adequate health coverage and access to medical care, and who are the most vulnerable to job losses. This, too, is a fundamental issue of both safety and equity. Concentrated poverty, economic inequality, and racial and economic segregation are not only morally unjust—they also provide fertile ground for pandemics to take root and spread. Economic inclusion and more equitable development are critical factors for the health, safety, and economic competitiveness of our places. Cities and local leaders can work with federal and state agencies, community development organizations and local foundations to target needed funds, support services and technical assistance ot these areas.

There is light at the end of the tunnel. In the not-too-distant future, the pandemic will end and our cities will return to something approximating normal. What we do over the next 12 to 18 months can ensure that our city and metro economies get up and running again while protecting themselves against similar scenarios in the future. This is a time when our cities and their leaders can and must show the way forward.

The City of Chewelah has been designated a certified Creative District by the Washington State Arts Commission. The Creative District program, which began just last year, is a platform for communities to grow their creative economies. A Creative District is a geographically defined area where art, cultural, social, and economic activity takes place. It includes cultural facilities, artists, creative industries and other businesses that support these activities. It helps to encourage job growth and educational and cultural opportunities.

With a population of 2,600, located 45 miles north of Spokane, Chewelah has approximately 90 community arts and cultural events per year. These events range from a traditional skills retreat that teaches blacksmithing and woodcarving to the Chewelah Chataqua, an annual arts and music festival drawing approximately 25,000 visitors to the town in mid-July.

“We are looking forward to utilizing the designation as a catalyst for Chewelah to become a “beacon” for artisans, entrepreneurs, tourism, and continued economic growth.”

—Mike Bentz of the Chewelah Chamber of Commerce.

The Chewelah Chamber of Commerce the lead organization, but the Collaborative Partners included business leaders, artisans, and cultural leaders. “The local Collaborative Partners are both humble and proud of this achievement,” Bentz said.

“We are looking forward to utilizing the designation as a catalyst for Chewelah to become a “beacon” for artisans, entrepreneurs, tourism, and continued economic growth,” said Bentz. “Since we heard the good news, the excitement level has become contagious.”

Creative Districts program manager Annette Roth said she’s pleased to see both cities receive certification.

“Although these communities are very different from each other, they both demonstrate how they can use a program like ours to create a vision for the future that is reflective of their community values and use their creative assets to grow their local economy”

— Annette Roth, Creative Districts Program Manager at ArtsWA

ArtsWA’s Creative District program supports designated communities with grant funding opportunities, technical assistance, training, wayfinding signage and more. The designation for each community lasts for five years.

The Creative District program began in 2018. It is a platform for communities to grow their creative economies. A Creative District is a geographically defined area where art, cultural, social, and economic activity takes place. It includes cultural facilities, artists, creative industries and other businesses that support these activities. It helps to encourage job growth and educational and cultural opportunities.

- 1

- 2